Working with my Zettelkasten is a constant evolution, as my needs change over time. It seems to be an endless journey to improve my personal knowledge management system. By chance, I discovered “Wardley Mapping” by Simon Wardley [1]. It’s a method for understanding how to develop your strategies. My first idea to learn more about this visual tool was to apply it to my Zettelkasten strategy.

Let’s take a closer look. A Wardley map allows us to visualize the Evolution of business components over time. It starts from the unstable beginnings to more stable, standardized components. These components fall into four stages: genesis, custom, product, and commodity.

First: Genesis components are novel and new. Second: Custom components exist for a specific use case with some proof of value. Third: Product components are standardized and reliable elements. And last: Commodity components are best practices, well defined, and widely used.

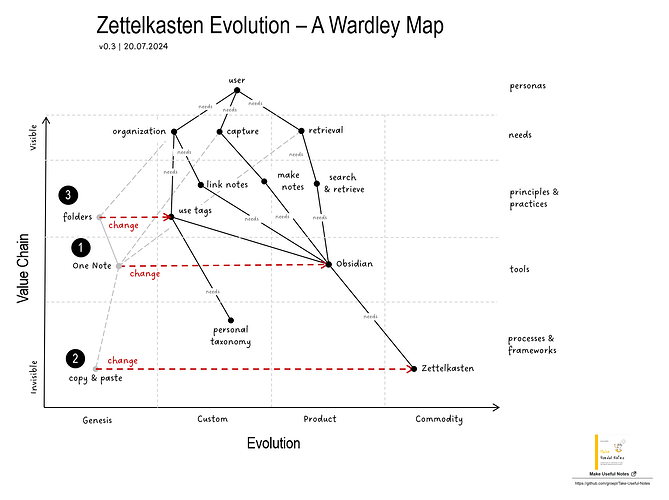

Figure: Zettelkasten Evolution - A Wardley Map, v0.3

In the Value Chain, the underlying methods and practices are implemented at various stages to enhance the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the system.

Developing a Wardley Map for using a Zettelkasten in my personal knowledge management involves outlining several components to understand and strategize my approach effectively:

- Purpose: Efficiently manage and leverage personal knowledge for continuous learning and productivity.

- Scope: Digital note-taking, linking ideas, research support, excluding team collaboration.

- User: Primarily self.

- User Needs: Quick note capture, efficient organization with tagging and linking, easy retrieval.

- Value Chain: From user to Zettelkasten.

- Wardley Map: Helps to visualize the different components and their current state in the evolution, guiding where to focus efforts to improve my personal knowledge management system.

And here is my story: (1) I started my changes to improve my personal knowledge management system by moving from OneNote to Obsidian two years ago. (2) The biggest change was my first contact with the Zettelkasten framework. (3) Here it was really hard for me to change my personal organization from thinking in “folders” to “tagging”.

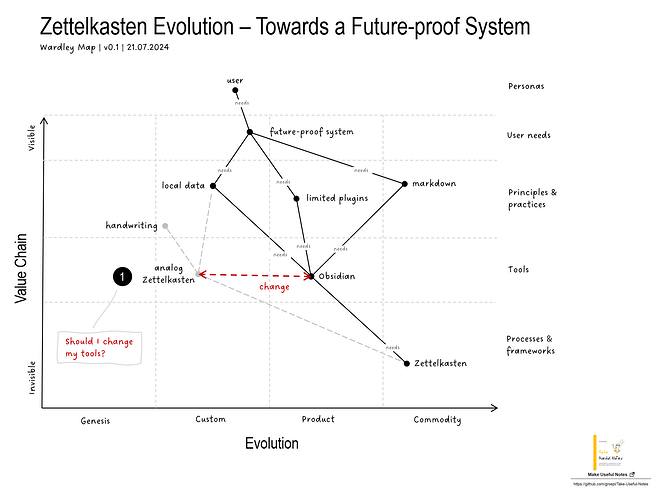

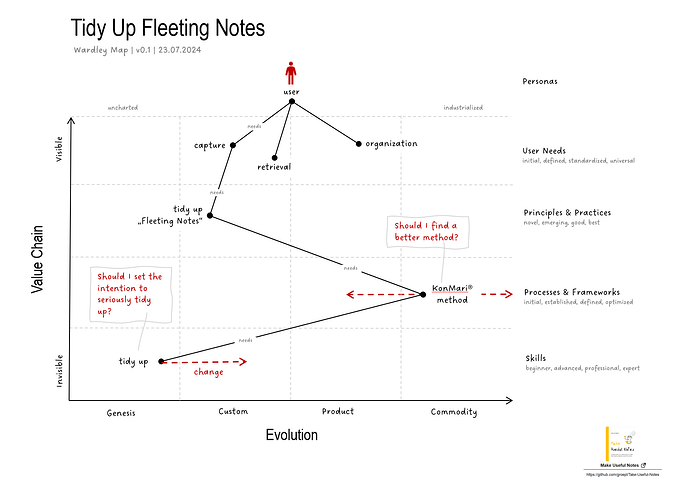

Now my current challenge is to use analytical reading [2] to improve my notes. And I’m sure I’ll need another Wardley map. As it is said by Simon Wardley: “There’s nothing wrong with you. Developing a strategy is just hard.”.

What will the next steps be? What are your recommendations?

References

[1] Wardley, Simon. “Wardley Maps.” Learn Wardley Mapping. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://learnwardleymapping.com/book/.

[2] Adler, Mortimer Jerome, and Charles Lincoln Van Doren. How to Read a Book. Touchstone edition. New York, Touchstone, 2014.

Related

More about the 12 Principles For Using Zettelkasten