This article stems from my previous reflections on the three organizational structures of “categories, tags, and folders.”

I’ve reorganized and shared these thoughts as a sort of interim summary.

Introduction to the Three Organizational Structures

- Category

In Obsidian, categories are typically implemented through standalone category notes. Each category is an independent note, and other notes establish their belonging relationship by pointing to the corresponding category note via metadata (YAML frontmatter) using bidirectional links (e.g.,category: [[Games]]).

This usage comes from Kepano’s example vault. For details, see: How I use Obsidian — Steph Ango

-

Tag

Tags are flat, non-hierarchical metadata markers. A piece of content can have multiple tags, and tags have no parent-child relationships. They are suitable for expressing attributes, states, or lateral associations of content. Examples:#Methodology,#Tools,#ToBeOrganized. -

Folder

Folders are physical storage structures that determine the actual location of files on the hard drive. Folders can be nested to form a tree-like structure, but they are primarily used for managing file storage and retrieval, not for directly expressing semantic relationships.

Use Case Examples

Taking the same note “Hollow Knight” as an example, here’s how the three organizational structures can be implemented:

-

Category Usage

In the metadata of “Hollow Knight.md,” use a bidirectional link to point to the category note to establish belonging:--- category: [[Games]] ---Here, “Games” itself is an independent category note that can aggregate all content belonging to this category. With plugins like Dataview or the upcoming core Bases plugin, you can quickly display all sub-notes under this category.

-

Tag Usage

Add tags to the note to express attributes or lateral relationships: Simply type#Games/Masterpiecein the body.This allows for quick retrieval of all “masterpiece games.”

The advantage of tags is their flexibility—you can insert them anywhere in the text.

However, they can also be more “chaotic” and “scattered” because all your tags are mixed together, and their meanings can vary widely. -

Folder Usage

Archive notes via physical paths, such as placing “Hollow Knight.md” in the following folder structure:Games/ Hollow Knight.mdThis method expresses belonging through folders but lacks the ability for multiple belonging and flexible queries.

Basic Comparison

| Category | Tags | Folder | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique? | Supports multiple | Supports multiple | Unique |

| Hierarchy | Builds hierarchy via note properties | Supports #a/b hierarchy |

Single-level hierarchy |

| Storage Form | Metadata (specific property with bidirectional links) | Metadata (tags) or inline in text |

Physical file path |

| Query Method | ["categories":xx] |

tag: #xx |

path:xx |

| Description Note | Bidirectional link to “category note” | None (can manually establish relationships) | FolderNote (folder-specific note) |

| Semantic Expression | Strong (can use property names to denote relationships, plus category notes can add explanations) | Moderate (requires personal understanding of tag meanings) | Weak |

| Example | categories: [[People]], [[Artists]] | tags: #people #authors | 3-Resource/Archives |

| Theoretical Quantity | Moderate (only create necessary categories) | Can be numerous, even more than notes (low creation cost, the “freest” option) | Keep minimal to avoid overly complex file structures |

| Precision | Broad categories | Theoretically the most precise and detailed (highest match accuracy) | Broadest (may lack type meaning, e.g., date-based directories) |

- Categories use metadata with bidirectional links to establish belonging, suitable for expressing “what something belongs to,” and support multiple belonging and flexible queries.

- Tags emphasize content attributes and lateral associations, suitable for expressing “what features something has.”

- Folders emphasize physical storage and management, suitable for expressing “where something is stored” (the weakest relationship among the three).

Category notes naturally support additional explanations or specific conditions for displaying sub-notes.

Conversely, tags can achieve similar functionality by manually creating a “tag description note” with the same name as the tag, though this is more cumbersome.

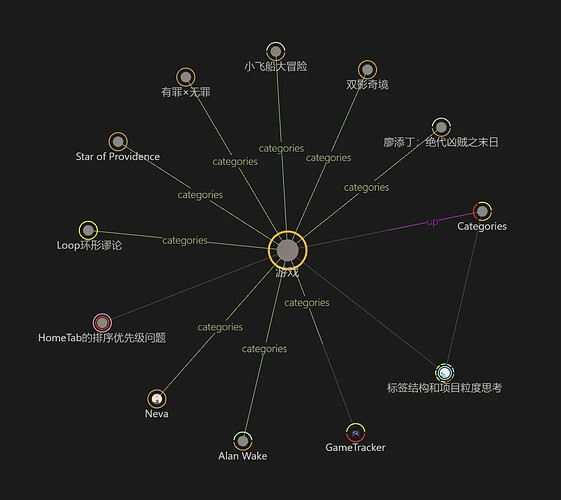

Another advantage of using categories is that in the knowledge graph (Graph), you can clearly see how different notes under the same category point to a central node.

Graph displayed using ExtendedGraph

Of course, displaying tags on the graph can achieve a similar effect, but tags feel more chaotic to me (numerous and broadly expressive). I prefer the controlled organization of category notes.

There are also specific plugins that can make folders appear on the graph.

This also shows that, most of the time, “tags” and “categories” can substitute for each other. Both can implement some features of the other, with the only difference being the level of effort required.

(The folder structure, due to its “single correspondence” limitation, often cannot replicate the features of the other two.)

Key Differences

Here are two critical differences.

I. Decoupling

Compared to categories, tags are more tightly coupled.

This mainly refers to “how much is affected when a change occurs.”

If a tag is modified, all instances of the tag need to be updated.

For example, Chongqing was originally part of Sichuan:

#location/China/Sichuan/Chongqing

When Chongqing became a municipality directly under the central government, it needed to be changed to:

#location/China/Chongqing

Renaming the tag would cause all files using this tag to be updated.

For category notes, only the province property of the Chongqing note changes from [[Sichuan]] to [[Directly-Administered Municipality]]. All notes originally with city: [[Chongqing]] remain unchanged.

II. Precision

As mentioned earlier, tags are overly broad.

For example, take the same category note [[Movies]]:

- For a movie note,

category: [[Movies]]means this is a movie. - For a study about a movie,

topic: [[Movies]]means its theme is movies. - Even when recording a friend who loves movies,

hobby: [[Movies]]means their interest is watching movies.

This is an advantage of categories: they can specify the type of relationship.

For tags, you can only have tags: #Movies, which conveys only “relevance” without specifying “how it is relevant.”

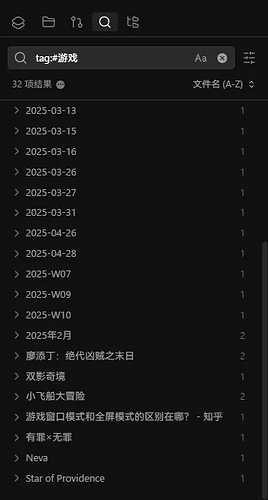

Since I also use the #Games tag in my daily notes, searching yields many “irrelevant” results.

Unless tags are specifically structured as Type/Games, it’s harder to distinguish “notes about games as a type.”

If you argue, “Tags can also use nested hierarchies to express relationships?”

For example, Type/Games for game-related notes, Topic/Games for studies about games…

This leads to the “chaos” problem—the same Games would be scattered across multiple sub-tags, and searching for #Games wouldn’t even find them.

Summary

Categories, tags, and folders each have their focus. In practice, they can be combined:

- Use categories (category notes + metadata bidirectional links) to organize the knowledge system, ensuring clarity and flexibility.

- Use tags to supplement attributes and lateral associations, improving retrieval efficiency.

- Use folders to manage physical files, facilitating archiving and migration.

Taking “Hollow Knight” as an example, my current approach is:

Create a dedicated “Games Database” folder, placing all game notes inside.

“Hollow Knight” points to the [[Games]] note, allowing all games to be displayed via backlinks.

It can also include statuses like completion time and playtime.

Finally, for further classification (e.g., “Masterpiece” or “Dropped”), tags are most suitable.

The original motivation for this article was learning about the category note structure and wanting to explore its relationship and differences with tags, as well as when each is appropriate.

After research and discussions with peers, I’ve arrived at this interim conclusion.

After using this system for a while, I feel it’s truly the most suitable organizational form for bidirectional-linked notes—arguably unique to them. I highly recommend interested users—especially those with specific requirements for note organization—to give it a try.

That’s all.